Population and demographics -- a theme of Malthusian fame -- is a classic topic in forecasting. It is perhaps the most readily available proof that the future actually can be predicted, as opposed to being completely under influence of chaos and capriciousness. By its very nature, demographic trends span at least a human lifetime, and allow us to project far ahead, provided that there are no major extinction events such world wars or pandemics. William Hague, a former UK foreign secretary, made the same point in an article last month in the Telegraph:

Demographic forecasts tend to be among the most reliable, partly because we already have a lot of information that will not change: we know how many 36-year-olds there should be in 2050 because they were all born last year. Furthermore, changes in birth rates normally take place fairly slowly, allowing reasonable projections to be made.

Hague paints a rather grim picture where population will explode in Africa and the Middle East, with mounting pressure from waves of immigrants seeking to get into Europe. We do not learn of the sources of his predictions in the article, but we can assume that they are partly based on works such as the 2015 World Population Prospects from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. That formed the basis for my weekend reading.

Total population of the Earth

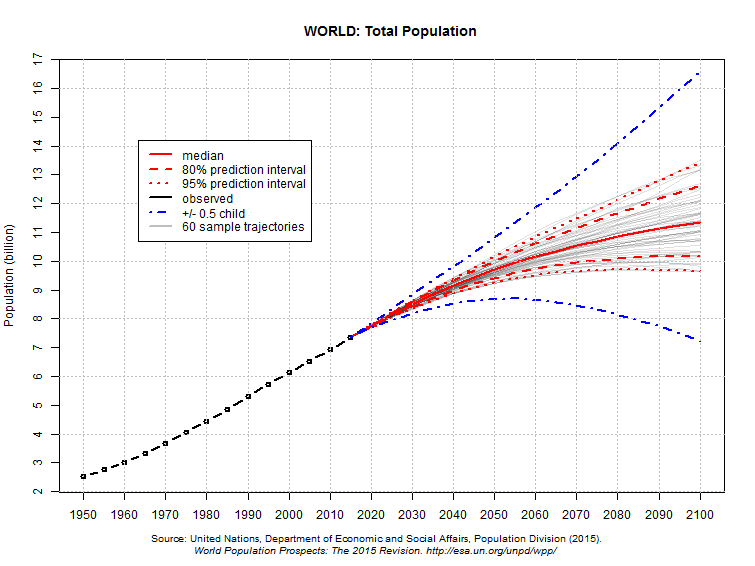

The big picture can be found by drilling down in the graph section until we find the chart "Probabilistic Projections / Population / Total Population / WORLD":

From a population of 7.3 billion today, the Earth is expected to house 9.7 billion people in 2050, and eventually fill up at about 11-12 billion past the year 2100. The population follows a logistic function, but in the near term, it is roughly linear, and there is no explosion of population, just a continued, decelerating boom. The uncertainty long-term is substantial, at least +/- 1 billion, and we see that even with a rather large decline in global fertility (-0.5 child), which is about the same level as seen in China and Japan today, the population will still grow until at least 2050.

But how can we be certain that this is an accurate forecast? In fact, the demographers themselves warn us not to take them too seriously. In an analysis aptly called What if the experts are wrong on world population growth?, Carl Haub, a demographer in US, writes:

It is customary in the popular media and in many journal articles to cite a projected population figure as if it were a given, a figure so certain that it could virtually be used for long-range planning purposes....That is far from a sure bet.

He continues to explain many of the underlying assumptions of population models, such as the so-called demographic transition, where it is taken for granted that developing countries will mirror the trends already seen in Europe, and rounds off by a fleeting mention of the fact that there can be no population growth without a sufficient supply of fresh water, food, and basic health services in the first place. The first point is important to keep in mind, given that we are now seeing that well-off and well-educated people in Western world are now choosing to have more children (see e.g. this article: Highly educated women no longer have fewer kids), which is contrary to the historical trend, but in this post I will rather delve deeper into the question of resources and the carrying capacity of the Earth as think it is important to contemplate how such a population increase would manifest itself in everyday life, and what the necessary conditions are for realizing it. What does it actually mean to have 9 or 12 billion people in a future world?

Food capacity of the Earth

The UN report states that "more than half of the global population growth between now and 2050 is expected to occur in Africa". Europe, on the other hand, is expected to have smaller population in 2050 than in 2015. In practice, most of the growth will be absorbed by a few countries, namely India, Nigeria, Pakistan, DR Congo, Ethiopia, Tanzania, USA, Indonesia and Uganda, and the trend is that most of the growth will be in urban areas (see World Urbanization Prospects, the 2014 revision). This brings to mind a picture where old cities expand, and new ones develop, across Africa and Asia. But we must keep in mind that cities are not self-sufficient in food and resources, so this shift from the rural to the urban means that the rural areas will have to produce a lot more food while employing essentially the same pool of farm workers, a development which can only happen by means of an increasingly industrialized food production. Also, as cities grow, new housing and infrastructure will need to be constructed, or at least upgraded. That seems to imply that eventually a surge in demand for industrial and energy commodities will reappear, even though today, that demand is very weak.

Returning to the question of food supply, we can start by looking at the situation today. It turns out that in terms of overall food production, the population on the Earth today could be adequately fed, given that access to food could be secured for everyone (chart 24 in the UN's FAO Statistical Pocketbook 2015 claims an overall food supply ratio of 120% for the world). Now, unfortunately, food distribution and security is a well-known issue yet to be resolved, so for various reasons, ca. 800 million people are considered undernourished today. A principle reason is war and local conflict, which is not likely to completely disappear anytime soon, but the fact remains that in the truly utopian scenario, we would not actually need to produce that much more food in order to support a population increase from 7.3 to 9.7 billion (+33%), as the ratio is already at +20% today.

In reality, though, food production is not evenly distributed across the world, and of the growing countries above, only USA and Indonesia have a positive net trade balance in food products (FAO Statistical Pocketbook 2012). So to sustain this population growth, we either need to see a drastic increase in the domestic food production in what is already today challenging growing conditions due to land erosion, climate change and water shortages, or rely on increasing world trade in food. Both of these conditions are intimately connected with two other classical utopian challenges: the first one is world peace (as mentioned above) -- it is a necessity for both global trade to work efficiently and for local food production to be stable; the second one is that global trade relies on cheap energy for transportation of goods across the world. There is possibly also a third condition related to global food trading, it also depends on free trade and efficient markets. Whether it is considered a utopian development depends, I guess, on the political view of the observer.

To make it more concrete: today, the two breadbaskets of the world are the United States and Brazil. They would have to supply a lot of food to the world market in order to support a growing world population. One complication is that Brazil's food exports mainly comes from the Mato Grosso area, which is far inland and landlocked. So while there is great potential there to produce huge corn and soybean crops, in practice, the output is constricted by a transportation infrastructure that is stretched to its limits and dependent on fossil fuels. There is also the issue of deforestation when expanding the farmland. Brazil is, of course, seeing the potential for increasing exports and is starting infrastructure projects to deal with the most critical problems, but currently Brazil is in a recession, and the world commodity prices are low, so we cannot expect rapid improvements as the investment climate will likely be unfavorable for some time to come. All things considered, "connecting Brazil's interior with the coast is an immense task that will take decades", as it is stated in an analysis by Stratfor, which is a good overview of the history and current situation of Brazil's infrastructure.

In conclusion, it is not clear to me how the world's population will just spontaneously grow to 10 billion. It certainly could happen, but seems to involve drastic efforts just in terms of food supply and land availability, as well as being highly dependent on continued political stability across the world.

Electricity production

The question of the world's future energy production in the face of peak oil, CO2 emissions and climate change is daunting and I will not attempt to span to much of it in this post, but rather stay at the very big picture. The availability of energy and electricity is intimately connected with food production. I want to exemplify this with the world summary of food production metrics in the FAO Pocketbook on pg. 48. There is an encouraging trend of increasing food availability over time from 1990 to 2014 (i.e. 2597 kcal/day per person to 2903 kcal/day), while at the same time energy consumption, global trade, and fertilizer use is increasing greatly, as well as the greenhouse gas emissions. It seems clear that food production is dependent on energy, both fossil- and biofuels.

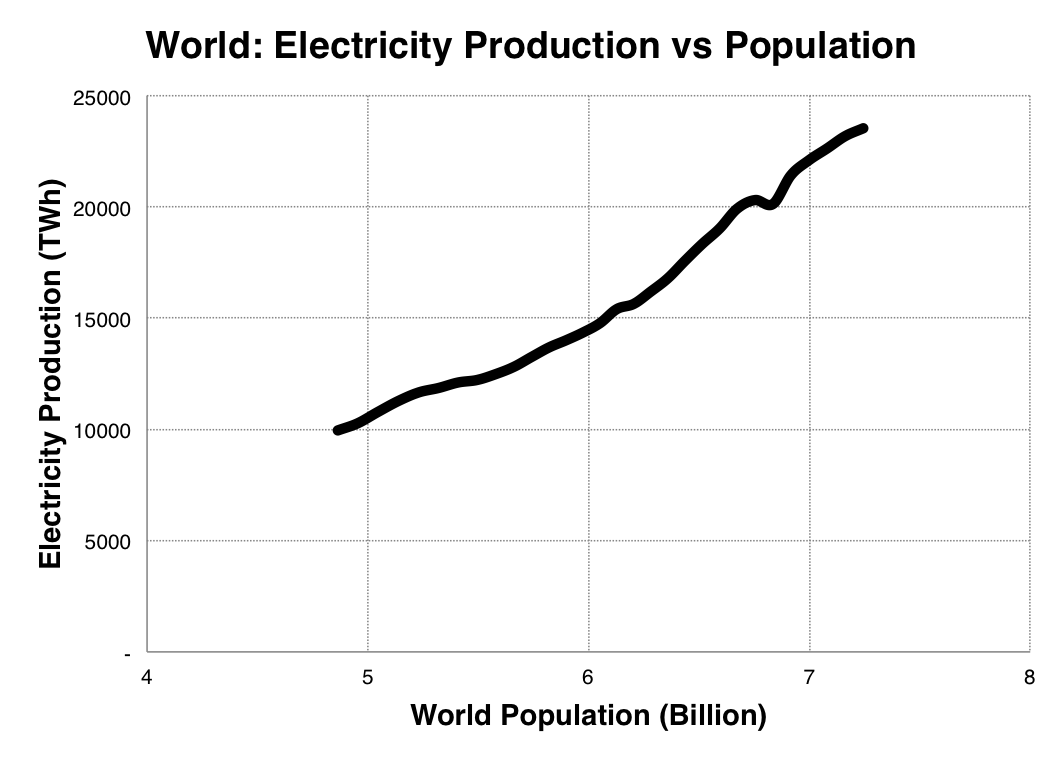

It is empirically clear, at least if we envision a future where GDP/capita and living standards are not declining, that more population also requires more electricity. This is evident if one plots the world's electricity production vs. the population. I have used data from BP's Statistical Review of World Energy 2015 and UN's population data as referred to above:

We can easily extrapolate the curve and arrive at a guess of how many TWh are needed to support 10 billion people. Surely, energy savings and improved efficiency can, and should be, explored, but it is doubtful if it can free up to 30% of extra capacity. I think the best estimates currently are around 10% overall for industrialized economies and developing countries would likely start building infrastructure from a more energy-efficient starting point, which makes the potential gain from energy efficiency even smaller.

In the context of reducing CO2 emissions and transitioning to renewable energy, I think it is often forgotten that not only do we need to replace existing energy sources from coal, natural gas, and oil (87% of all energy!), but also build out the capacity by 30% relative to what we have today in order to meet the demands of an increasing population by 2050. That is an even more formidable challenge. Spontaneously, the thought comes to mind that something will have to give in: either population growth will stop, or many developing nations will be faced with the choice of accepting certain poverty due to energy shortages or an uncertain hardship suffering from pollution and climate change.

The aging population

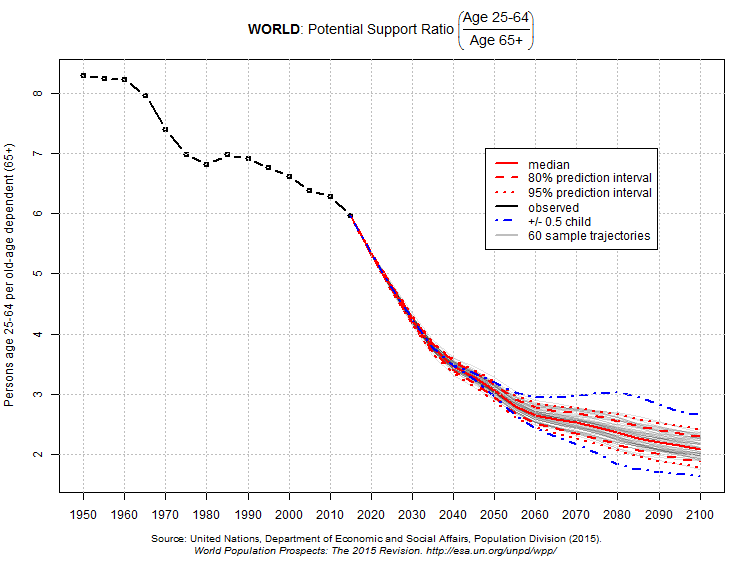

Finally, it is worth looking not just at the total population, but also its composition. A well-known prediction of demographic research is the looming pension crisis , which refers to the shrinking number of tax-paying workers for each retiree as a result of an aging population (for an overview of the concept, see e.g. the Wikipedia article). It is not related to the increase in population per se. On the contrary, it is actually the effect of an opposite trend reflecting a shrinking population in the far future due to reduced fertility. Yet, it is perhaps one of the most striking and easy to relate to predictions. In the World Population Prospect, the pension crisis can be visualized in the probabilistic projection of the Potential Support Ratio:

The number of workers per retiree is expected to decrease from 6 to 3! This will put pension systems, or the support burden by relatives, under enormous pressure, as a priori, the inflows of funds would need to double in order to keep the same retirement age. Alternatively, the retirement age will have to be raised sufficiently for the funding to balance out. There is some indication that the improving health and longer lifespan of the future seniors (basically the author's own generation) might allow us to work for longer, but it is far from certain that it will be enough to balance the system. My current understanding is that there are no magic bullets that will solve the problem apart from raising taxes, postponing the retirement age, and increasingly relying on private pension plans for those that can afford it. The International Monetary Fund expresses it, shall we say, more abstractly, as a "longevity risk" in the Global Financial Stability Survey from 2012:

Longevity risk threatens to undermine fiscal sustainability in the coming years and decades, complicating the longer-term consolidation efforts in response to the current fiscal difficulties.

To understand the magnitude of the problem, we can compare to the support ratio of Japan today, which is around 2, and which passed below 3 in the early 00s. Many Western countries will see a similar development. Having not visited Japan, and not really being able to read Japanese, I had to resort to browsing around Nippon.com trying to get a feel for the situation of the elderly in Japan today. It seems like the Japanese society is still holding up, but poverty is a becoming a real, but often hidden, problem, and many people experience social isolation. Perhaps to combat the isolation, they choose to do part-time jobs past retirement, often unrelated to their previous career and with less pay. Eventually, as age really advances, part of the burden of the care traditionally falls on younger relatives (read daughters-in-law), which likely slows the ballooning social security and healthcare costs somewhat. Yet, I wonder for how long the situation is sustainable, because the support ratio is still dropping in Japan, and from the fiscal point of view, the economy is still struggling. The picture we get from Japan is that the pension crisis will likely not end in a complete disaster of the kind where people are dying on the streets, but it will certainly reshape the societies. It will inevitably push back some of the advancements of the welfare state, such as full retirement, and reintroducing family responsibility for the care of the elderly.

Conclusions

- World population could grow to 10 billion as early as 2050.

- Food is not the primary limitation; the real challenge is going to be electricity and fuel for transportation. If that cannot be met, the end result is going to be increased poverty.

- The trends point to increased urbanization. Fortunately, this will mitigate some of the effects of peak oil and the conversion from carbon-based fuels to renewable energy, as it is likely to reduce the need for transports.

- If electricity and energy can be provided, and the GDP/capita increases in developing countries, the economic power will inevitably shift from the Western world to Asia and Africa.

- Population will decrease in Europe; demographics indicate that Europe will be following the path of Japan with an aging population and slow economic growth.