The bleak projection of future oil use in a previous post made me look more into what was actually agreed upon at the landmark Paris meeting on December 12th 2015. The full text of the accord is available, and for quick bullet point list of the key elements, I recommend the summary by the European Commission. I read the accord and looked at the pledges made by different countries, also called the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs), in an effort to anticipate what our future society might be like. Here, I am assuming a continued state of relative peace, like today, but it is not unlikely that climate change will lead to mass migrations and local conflicts, which subsequently could escalate into full-scale wars.

The Paris Accord in Short

The cornerstone of the agreement is found in Article 2:

(a) Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 ˚C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 ˚C...

The supplemental mention of 1.5 degrees was a more ambitious goal than expected and was heralded as a victory by environmental organizations and more progressive countries (such as in the EU, where it will be easier to cut CO2 emissions due the declining population and loss of manufacturing capacity). Yet, critics pointed out that not much was actually committed to in terms of actual specific measures. There is some truth to this, because in the wake of point (a) comes two important reservations, namely the sections (b) and (c):

(b) [Taking measures] ... in a manner that does not threaten food production;

(c) Making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development;

These, in my opinion, show concern that drastic reductions in CO2 emissions could restrain food production and incur considerable costs. Presumably, these reservations were put in by developing countries. They have drawn a line saying that starvation is not an acceptable side effect when cutting CO2 emissions. At first glance, it seems like a self-evident and necessary reservation, but it reveals that the underlying priorities are still, as they have tended to be throughout history, human welfare first, and the environment second. When push comes to shove, the implication is that we will rather accept a warmer climate and wide-ranging environmental changes than threatening food security. What I find interesting is that reasoning like this presumes that there is such a choice available in the first place, which might not be the case.

The meaning of "finance flows" in Section (c) is becomes more clear when running one's eye over Article 9, which proclaims who are responsible for emanating the flows of finance:

As part of a global effort, developed country Parties should continue to take the lead in mobilizing climate finance from a wide variety of sources, instruments and channels, noting the significant role of public funds, through a variety of actions, including supporting country-driven strategies, and taking into account the needs and priorities of developing country Parties.

Evidently, the main burden falls on the developed countries, but there is no binding clause on how much money that will be committed (although at least 100 billion USD per year is mentioned elsewhere). Also, I cannot help to note the left-leaning political stance in the text, "significant role of public funds", suggesting that there is no other way to counteract the climate change other than to mobilize taxpayer money. Apparently, private enterprise alone is not enough to resolve the climate problem. This seems to validate the claims from the right side of the political spectrum that climate change mitigation is a leftist movement, which is unfortunate.

In general, I concur with the opinion that the agreement seems half-hearted. It is surely an important statement of will, but less of an actual commitment. We will have to wait a few years before we can discern its de facto ambition. In any case, though, there are clearly big changes on the horizon. To live up to the objectives set forth, we are essentially talking about reshaping perhaps half of the world's energy infrastructure, transportation systems, and a considerable part of existing housing. It will certainly be expensive, and take its toll on the world's economy, as alluded to in Article 2 section (c), so in this post I would like to look at what needs to be done to fully implement the Paris agreement and how the world would change as a result of it. The cynics already call the plan science fiction, but perhaps it can be done?

I will start by looking at the path of projected CO2 emissions in order to reach the objective of at most 2.0˚C degrees warming and what it means for the energy production. I will then look into the actual pledges that the countries have sent in ahead of the conference. What are the current plans to reach the goal? But in doing so, we must remember that the pledges submitted up until now are in many cases not sufficient to reach the goal in the first place. Per the agreement, they are to be updated by 2020 at the latest, with more severe measures put in place.

Impact on the Energy Production

Limiting the global warming to 2.0˚C requires bringing down the CO2 concentration to approximately 350 ppm (there is some uncertainty in the so-called climate sensitivity to CO2) compared to the level of ca 400 ppm today, which is rising by 2 ppm/yr or so, at least according this paper from 2008 James Hansen et al. The timeline and pace of CO2 cuts in the Paris agreement is not specified, but to get a feel for the pace, we can look at the the European Union, which aspires to reduce CO2 to 40% below 2010 levels until 2030, and to 60% below by 2050. Others would likely go about a bit slower, but we are basically talking about a 25-50 year horizon.

In the Hansen paper referred to above, they posit that coal power is what has to go:

The only realistic way to sharply curtail CO2 emissions is to phase out coal use except where CO2 is captured and sequestered.

Coal is clearly seen as one of the greater evils in the climate change community, so I too suspect that the choice will ultimate fall on coal, simply because the technology exists today to replace electricity generation by coal by something else, at least in theory, for example by a combination of other sources such as nuclear, solar, hydroelectric and wind power. Completely phasing out gasoline, diesel, and natural gas (for heating) in such a short time as 25 years, on the other hand, seems like an insurmountable task, as there are no viable replacements for liquid transportation fuel today. Gas heating could be replaced, but there is a vast infrastructure associated with it, which creates a lock-in effect, and it is also questionable how much would gained by doing so, given that gas heating is actually quite efficient.

The total amount of CO2 released from coal power is around 40% of emissions (see section 3.1 in Trends in Global Coal Emissions 2015), so phasing out all coal power, and capping every other CO2 emission (despite a planetary population increase of a 1 billion people) would take us to the first goal of reducing emissions by 40%. The question is how viable it is in reality? In the concluding paragraph of the paper referred to above, they admit that: the most difficult task, phase-out over the next 20-25 years of coal use that does not capture CO2, is Herculean, yet feasible. Unfortunately, there is no elaboration of what the feasible solution could be, other than possibly slowly taxing coal power out of existence (although Hansen has been critical of the cap and trade scheme as such, he is not against taxing per se).

The crux of the matter is that a rapid phase out of coal power cannot happen without shutting down existing power plants prematurely and thus destroying investments in existing infrastructure, which by itself will put even higher demands on renewable electricity generation. I found this presentation by Osamu Ito on coal emissions from an International Energy Agency (IEA) workshop quite helpful in further understanding the problem. One of the observations were that:

Newly install power stations, in the absence of policies to encourage their early retirement, will continue to operate and emit large quantities of CO2 until 2050. Thus, even if no coal plants are built after 2015, total emissions from all coal-fired plants would be almost equivalent to 2000 level.

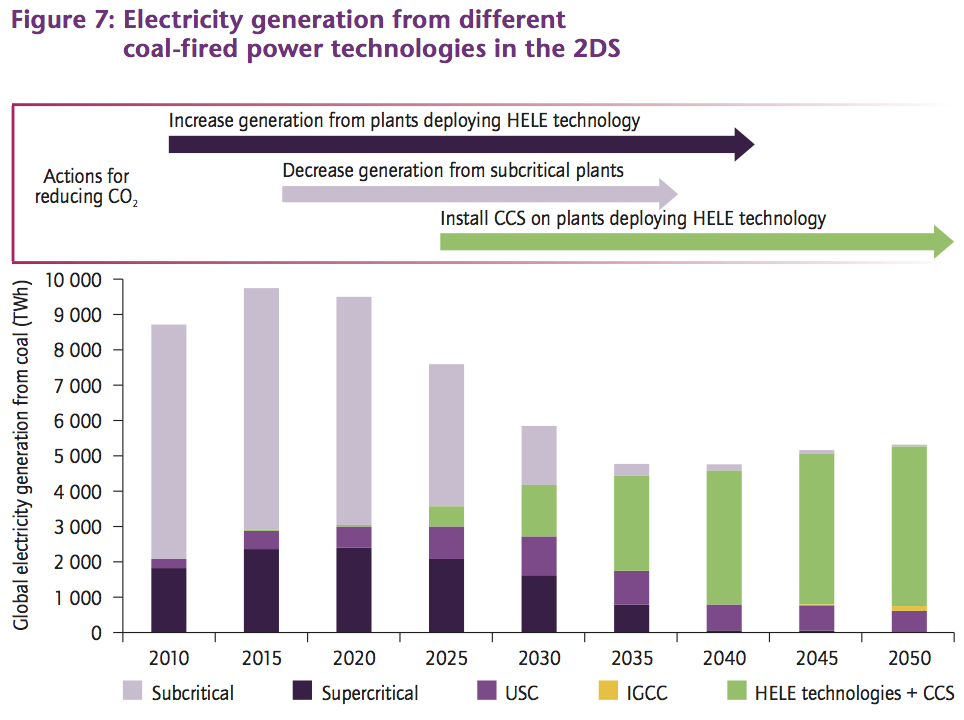

A similar hypothetical scenario is explored in figure 7 in the IEA technology roadmap for coal power 2013, where it is shown what it would take to reach the maximum 2-degree warming target in the context of coal power:

Copyright 2012 OECD/IEA 2012 Technology Roadmap High Efficiency Low Emissions Coal-fired Power Generation, IEA Publishing. Licence.

In the figure, "USC" refers to more efficient ultra-supercritical plants, "IGCC" to potential plants with integrated gasification combined cycle, and "HELE+CCS" to any of these or other future improvement combustion technologies combined with carbon capture. It is projected that the subcritical plants will be completely phased out during 2020-2035 (perhaps due to a worldwide ban post 2030), and carbon capture solutions will be installed from 2030 and onward. Yet, despite the optimistic assumption of carbon capture, the end result is that by 2050, the total electricity output from coal power will have decreased to half of what it is today. Based on this, it is highly likely that electricity prices will have to increase in the future to support a transformation like this, partly because the early retirement of old plants will hurt profitability in the utility sector and partly because of the increased cost of carbon capture solutions. That will subsequently limit economic growth, as there is still a strong link between growth of GDP and availability of electricity (this, so-called elasticity, or correlation, is typically between 0.5-1.0).

The demise of coal is also especially relevant for dynamics of the electricity generation in the whole grid, as much of the baseload capacity comes from coal and nuclear power and cannot straightforwardly be replaced by solar and wind power, being of a more intermittent kind. So without sufficient baseload, we will have to accept intermittent electricity shortages and would have to learn to live with a much more opportunistic usage of electricity. I can imagine, for example, that more flexible working hours might be necessary, both to smoothen out the energy usage, but also to deal with increased use of public transport. At home, we might have to get used to checking the electricity forecast, just like we have the weather forecast today, and buy smart appliances that automatically turns on when the electricity price is low. Part of this is already happening today with home automation technologies and the "smart grid". For the manufacturing and the industry sector, it will be much more difficult to adapt, because they often operate 24/7 as many industrial processes cannot be turned on and off suddenly. One thing I can see happening is that it could be possible to optimize the energy usage by separating the machine intensive parts of manufacturing from the labor intensive parts and e.g. build up a big store of generic pieces during one season, and then assemble and customize them into finished products later. Such a development will destroy the current just-in-time production that we have today, and move the economy more towards central planning, which historically has been inefficient, but the illusion of instant production and delivery might still be kept by the greater involvement of the customer in the design of the product.

In the end, the conclusion is that our society is built on cheap, readily available energy. A transformation is certainly possible, but there is no free lunch, such a transformation will come at cost, and who will pay? My impression is that many of the environmentalist groups hope that this development will be the end of the big oil and energy companies; they are the one that will have to pay for it, for past sins, so to speak. But, pragmatically, is it not likely that there will just be "Big Solar" and "Big Wind" to replace them instead? Someone will have to build and deliver all the renewable energy, and to do that there needs to be economic incentives, either through market mechanisms or state interventions. The whole issue is also complicated by the fact that much of the pension money is placed in safe, dividend paying stocks like utilities and energy. So windfall taxes cannot work without destroying retirement plans, or equivalently, being passed on to consumers. There is no way around the fact that retooling our energy factory will be expensive and take a bigger slice of our income, no matter how the costs are presented.

A Look at the Pledges of Individual Countries

The national (or federated) plans for reducing CO2 emissions in line with the Paris agreement were submitted ahead of the meeting during 2015. These are called INDCs, "Intended Nationally Determined Contributions" and can be found on the United Nations home page.

The European Union's pledge states clearly that their aim is a reduction of emissions by 40% by 2030, compared to 1990. The EU uses the year 1990 as baseline, which makes it even more ambitious, but given the expected population decline in the EU, it might be possible. The rest of the pledge is much less concrete, for example, agriculture and forestry policy will be provided later. In an attempt to cheer us up, the document proudly announces that

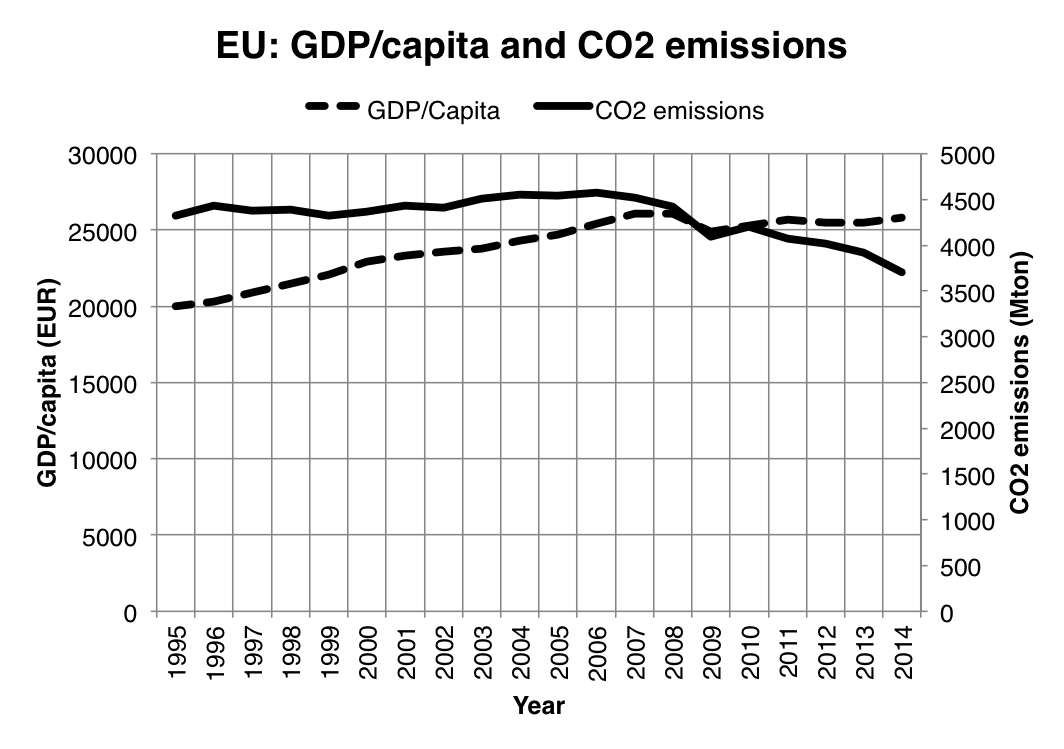

The EU and its Member States have already reduced their emissions by around 19% on 1990 levels while GDP has grown by more than 44% over the same period.

While this statement is accurate and looks encouraging, a look at the underlying data shows that the EU's CO2 emissions started decreasing after 2006, perhaps as a result of the financial crisis, but since then, GDP/capita has actually been flat in the EU.

Now, correlation is not causation, but it is interesting to see the EU managed to bring down the CO2 emissions substantially, while at the same keeping GDP/capita essentially flat. This is good, or bad, news depending on the perspective. On one hand, there seems to be little economic growth, as measured by GDP/capita, without the extra energy and its associated CO2 emissions. On the other hand, it shows that there is much potential for the rest of world to "decarbonize" without sacrificing existing living standards.

The United States is also very sketchy in its INDC and refers mostly to other existing documents such as the Clean Air Act and the Energy Policy Act. What I found interesting, though, was the mention of a presidential decree of reducing CO2 emissions from "Federal Government operations" to 40 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. The implementation plan is quite specific and contains measurable goals, so it is something I will put on my reading list.

Japan, on the other hand, has a much more detailed INDC. There are bullet lists of actions in several areas such as industry sector, residential sector, transport sector, etc. Japan is probably one of the countries which will most easily adapt to reduced CO2 emissions due to the declining population, relatively low economic growth, and a high proportion of nuclear power generation already present, so their plans should be viewed as a best case scenario. I came across a great overview and analysis stemming from the Systems Analysis Group at the Research Institute of Innovative Technology for the Earth (RITE) in Japan. Among other things, they point out that much of the government's plan in the INDC relies on massive improvements in energy efficiency and a low reliance on energy for economic growth: Japan's total power generation is expected to be roughly the same in 2030 and in 2014, despite an assumed economic growth of 1.7% per year. In addition, the power generation costs are expected to remain about 50% higher than before the great earthquake for the foreseeable future due to the increased costs associated with transforming the energy grid, even though the nuclear power plants are planned to be recommissioned.

One hard-hitting measure from Japan's INDC is a massive, almost 40% reduction of emissions from the commercial and residential sectors. Japan's industry sector is already very energy efficient, so they can only pledge 7% there, but it looks like life at home and the office is going to be a lot less convenient. I can only assume that this will involve cutbacks on electricity use everywhere and a significantly lower use of air conditioning (in the summer) and heating (in the winter), extending the Cool Biz and the Warm Biz concept to cover the entire society, perhaps ending up like some parts of China, where it is common to put more clothes on once inside the apartment. It is interesting to speculate how the 40% reduction will be enforced in practice: the Japanese office workers seem to be suffering already with 28 degrees indoors. Will people simply not be able to afford to run the air conditioner at too low temperature due to the price of electricity? Or will there be some kind of regulation of air condition units? Or perhaps a centralized control through the "smart grid"?

The emissions from the transport sector in Japan are also supposed to be reduced, by 28% to 2030. The main measures are improvements in: fuel economy, which can only happen through replacement of old cars for new, most likely smaller, ones; promotion of next-generation automobiles, which I interpret as a switch to electric cars, perhaps through tax incentives; a multitude of efficiency reforms such as promotion of public transport, increased use of railways, automatic driving, eco-driving, collective shipments of goods, and car sharing; and special economic zones. It is unclear to me how the last one of these will reduce CO2 emissions directly, perhaps indirectly by attracting financial and service businesses through tax credits?

If we hypothesize that out of the 28% reduction in the transport sector, 20% comes directly from a change of vehicles, and the remaining 8% is a combination various efficiency improvements in traffic patterns, it means that 20% of vehicle pool needs to consist of electric cars by 2030. Given that the average life of cars is perhaps 20 years, the replacement cycle of regular cars needs to very aggressive in the future, because the share of electric vehicle sales in 2012 was still only around 1% (according to the IEA Global EV Outlook) . Alternatively, there might just be a lot less cars in the future, presumably because people cannot afford to drive them?

Furthermore, the range of efficiency measures is likely to result in slower and less flexible transports. Transports can in general be optimized by doing them in bulk, and by doing them slower. That is relevant given the recent years trend in online shopping, which relies on fast shipping (and especially the ability to return unwanted goods). It might be difficult to sustain that trend, while at the same improving the efficiency in goods transport sector. For a relatively compact country like Japan, it might not be a big problem, but for geographically larger countries like China and the US, same or next day delivery options might be a luxury of the past.

Final observations

After looking more into the Paris climate accord, I think it is not utterly absurd to posit that the end of fossil fuels and oil is near, like I did in the previous post. The goals laid out are very ambitious. In fact, they are so ambitious that it is difficult to see how they can be implemented without tearing down existing technology and infrastructure, as opposed to just phasing it out as new technology becomes available. That is likely to create great tensions in society and create much pain ahead. In hindsight, it is quite ironic that the end of the modern era based on oil might come, not through peak oil, but through political decree. The new society that emerges will certainly be high tech, but in a very different sense from today. High tech may not necessarily mean a higher living standard, but rather a more energy efficient living standard, perhaps lower than today.

I am deliberately evoking more apocalyptic imagery here, because I feel that the messages we are getting from environmentalists and politicians active in the climate change cause are sometimes very naive and misleading. I would like to stray a little bit into politics here, even though I normally try to avoid it on the blog. For example, if we visit the web page of a high-profile organization such as the WWF and read about climate change, we are told that:

- "We can stop this."

- "It is fixable!"

- "We have the knowledge and the technology. We just need to make it happen."

- "We know what needs to be done about it."

There is further talk about "low-carbon living", and how it is actually better than our current way of life. I quote:

We are building a better, more sustainable world for people and planet. Moving away from our dependence on fossil fuels offers us a chance to rebuild the way we live so that it's not just greener, it's BETTER.

It would be interesting if they actually have a plan to rebuild the entire way we live, but let us be honest, after reading the Paris accord (which the WWF supports) and analyzing it, a world free of fossil fuels could also mean:

- Working in a 30+ degrees office in the summer (depending on the climate) to conserve energy.

- Coming home to a cold apartment in the winter for the same reason.

- Having to get rid of half of your electric appliances, because there is a building limit on electricity consumption, enforced by the landlord or the municipality. You could get new energy efficient ones, but they are much more expensive due to the "CO2 generating appliance value-added tax". In any case, your electricity bills are up at least 50%, so you don't want to add to it.

- Not having a car, because you cannot afford an all-electric car and you would need to get a special permit to have a diesel car. Cars are a big hassle anyhow, because there are no parking lots near where you are living. The city planners decided to remove them to create a "green open society".

- Relying on a extremely crowded public transport system to get around. Think London or Tokyo in rush hour, but all the time!

- Suddenly being called in to work by the boss for an extra night shift, because the electricity situation is "favorable" right now. You would love to say no, but need the money for retirement savings (see below) and utility bills.

- Giving up online shopping, because delivery times are so long, and all the packaging adds to the waste disposal fees. It is also highly inconvenient to return goods.

- Eating drastically less meat. Out of season vegetables are a luxury, because of the transport costs, which adds a lot to the price.

- Seeing your retirement plan go bust, because the 7% per year yield that it was based on disappeared when there was no electricity for economic growth.

I could give more hypothetical examples, but these are some of the changes likely to happen if there are no cheap alternatives to fossil fuel energy available and the Paris measures are implemented. Yes, we could do it, just like the WWF is saying, but the cost is high and far from just an easy "fix" as it would mean giving up our present standard of living. Personally, I hope that nuclear power will be eventually re-evaluated from an environmental point of view, as it has a very low carbon footprint.